Submitted by COL John Dietrichs

By TonyWoodlief

May 19 2017 7:O2 p.m. ET

COMMENTARY

Charity for All? Not in Today’s Debates

Over Civil War Memorials

ln a world of demons and angels, we can’t agree on who’s which. Most of us are somewhere in between.

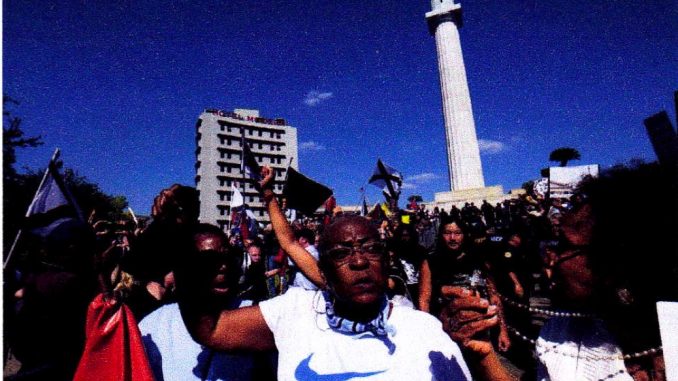

The city of New Orleans on Friday dismantled its statue of Robert E. Lee, the last of four Confederate monuments to come down. The removals have divided the community along familiar lines. One camp denounces the monuments as tributes to white supremacists. The other argues the memorials honor men who protected their states from an intrusive federal government. Is it possible that both sides have a point?

In April 1861, as war between North and South became inevitable, Col. Lee had to pick a side. He asked his mentor, Gen. Winfield Scott, if he could stay on the sidelines. *I have no place in my army for equivocal men,” Scott replied. Lee resigned from the U.S. Army two days later. “Save in the defense ofmynative Statf the Virginian wroteto Scott, “I never desire again to draw my sword.”

Nearly l5O years after his death, Lee’s reputation glows in the South. The Southern Povertylaw Center (SPLC) notes that nearlyhalf the 1O9 public schools named for prominent Confederates have Lee’s name over their doors. His decision *was honorable by his standards of honor,” opined Lee biographer Roy Bl,ount Jr. Even Lee’s rrilitary rival Ulysses S. Grant said after the war, “I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantl5r, and had suffered so much for a cause.” Though he added, “That cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people everfought.”

The nuance Mr. Blount and Grant expressed is noticeably absent in discussions of what to do about monuments honoring the Confederates. Rien Fertel, writing in the Oxford American, called Lee’s New Orleans statue a “traitorous golem.” When New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu made good on his promises to remove the statues, he had to send masked cityworkers, under cover of darkness and police snipers.

This maybe onlythe beginning. Aceording to the SPLC, there are more than 1,5O0 “publicly sponsored symbols honoring Confederate leaders, soldiers or the Confederate States of America in general,” and some 7OO such’monuments and statues on public propert5r.” More damning the SPLC says the preponderance emerged not immediately after the war, but during “the first two decades of the 2oth century and during the civil- rights movement.”

Facts are not always the SPLC’s strong suit. A partial examination of its list for my home state of North Carolina revealed several omissions of monuments erected in the Igth century. These include a 7S-foot tall monument, replete with stolen Unisn cannon, sitting in plain sight on the capitol grounds in Raleigh. Other monuments rose at later dates but hadbeenplanned foryears. One, in HollySprings, was built bya CivilWar veteran to honor local fallen soldiers from three wars and sits on private church property.

And there are some outright falsehoods. The SPJ,C wron$y claims that the Universit5r of South Carolinat Longstreet Theatre is named after Confederate Gen. James Longstreet. In reality it takes its name from the school’s ninth president, whose first name was Augustus. There’s no telling how many errors a systematic review of SPLC’s data would reveal.

But why quibble over facts when righteousness is at stake? Yale historian David Blight argued in a recent interview with Slate that many Civil War “facts” are actually elements of the “Lost Cause” myth. According to Mr. Blight, this myth romanticizes Confederates as guardians of old-world honorwho faced awell-armed Northern industrial machine bent on trampling states’ rights.

The problem with calling this a postwar myth is t\at ifsall well-established in the antebellum record. Southern leaders repeatedly claimed they had a right to sustain slavery and that the North was abrogating a traditional and constitutional balance of powers to undermine that right, as well as others. Was the war an indefensible defense of an evil and unjust institution? Certainly. Were the men who started it also motivated by grievances beyond slavery? Absolutely.

Then there are the common soldiers, frequently the ones honored in municipal monuments. A great many of them condoned slavery. Without question, they were also animated by what they believed was a threat to their homes and personal liberty.

Most people seem to need this debate to be more simple. Not only Ivy League professors and descendants of Confederate veterans, but also those who should knowbetter. Maybe Americans’ deep-rooted Puritanism drives them to view every person as either glorified or damned.

And so we spiral down this Stalinist path of history-flattening and monument-erasure, one side waving a battle flag that Robert E. Lee himself renounced the other insisting that every man who wore graywas little different than Leonardo DiCaprio’s caricature in “Django Unchained.” Americans long ago abandoned Lincoln’s admonition-malice toward none, charity for all-and in some important ways the U.S. is less united today than in 1866.

In a world of demons and angels, we can’t agree on who’s which. And we don’t have the charity in our hearts to admit most of us are somewhere in between.

Mr. Woodlief is a writer in North Carolina. Appeared in the May. 20 2017 print edition.

Copyright 2017 Dow Jones & Conpany, lnc. All Rights Reserved

This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, visit http://www-djreprints.com.

(The Old Guard of the Gate City Guard is a non-profit, non-commercial organization)